The enduring appeal of Sherlock Holmes owes as much to his steadfast companion, Dr. John Watson, as it does to the Great Detective himself. As created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in the late 19th century, the Holmes-Watson partnership has become a template for countless detective duos. Traditionally portrayed as a war veteran, medical doctor, and the loyal chronicler of Holmes’ cases, Watson serves as a moral anchor and emotional bridge between Holmes and the world.

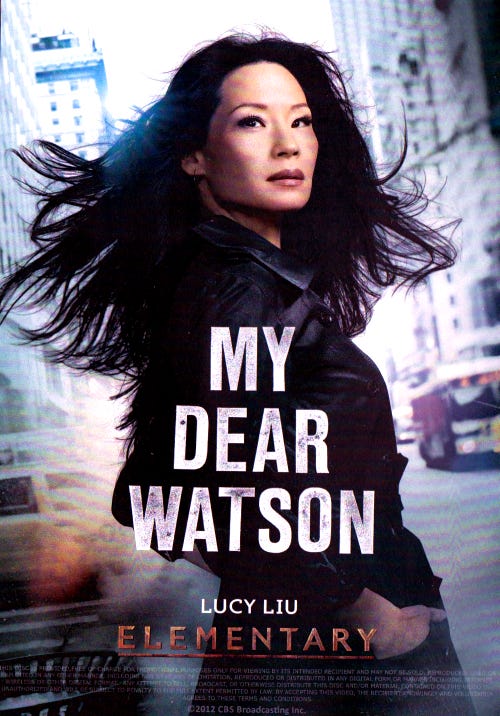

But what happens when this dynamic is altered by gender-swapping Watson from male to female? Contemporary reimaginings—such as CBS’s Elementary, which features Lucy Liu as Joan Watson—have explored this question to great effect. The result is not a mere casting novelty, but a fundamental shift in narrative chemistry, emotional depth, and social commentary. A female Watson offers new dimensions to the Holmesian universe—dimensions that are more viable in a modern setting than in the constraints of Victorian society.

In Conan Doyle’s canon, the friendship between Holmes and Watson is built on mutual respect, emotional restraint, and intellectual complementarity. Their bond is deep but platonic, reflecting the cultural norms of Victorian masculinity. Watson admires Holmes’ genius while gently questioning his eccentricities, and Holmes relies—though rarely admits it—on Watson’s steadfast loyalty.

Introducing a female Watson into this relationship transforms the emotional texture. In a modern setting, such as Elementary, Holmes and Watson evolve from mentor and chronicler into something more nuanced—equal partners with distinct emotional languages. Joan Watson, for example, challenges Holmes not only intellectually but emotionally, urging him to grow in empathy and self-awareness. The gender difference invites a broader range of interpersonal dynamics—vulnerability, caretaking, emotional tension—that would be implausible or taboo in Victorian England.

In a 19th-century context, a female Watson would face rigid societal boundaries. A woman living and working with a man outside of marriage would provoke scandal. Her participation in investigations—often involving criminal underworlds, physical danger, and police contact—would be severely limited by gender norms. Unless written as a radical outsider, a disguised figure, or a woman of extreme privilege, a Victorian-era female Watson would strain credibility within the period’s social framework.

The investigative model of Holmes and Watson traditionally places Holmes as the deductive genius and Watson as the practical facilitator—conducting interviews, offering medical insight, and grounding Holmes’ more outlandish ideas in real-world logic. When Watson is gender-swapped, this division of labor evolves.

Modern female Watsons often bring heightened emotional intelligence to the role. Joan Watson, for instance, begins not as a detective but as a sober companion and former surgeon, highlighting her care-oriented skill set. Her presence shifts the narrative from pure deduction to emotional rehabilitation and human connection. Holmes remains brilliant, but Watson becomes essential in navigating interpersonal subtleties—reading emotions, building trust, and seeing patterns in behavior Holmes might miss.

This shift leads to a more collaborative model. No longer the sidekick or biographer, the female Watson becomes a true co-investigator. Holmes may still dominate deductive leaps, but Watson often excels in intuition, empathy, and ethical discernment. This division deepens the storytelling by providing not only intellectual puzzles but also emotional stakes.

In a Victorian setting, these strengths would be undercut by limited access to social and professional arenas. While a male Watson could visit crime scenes, hospitals, and police headquarters unchallenged, a female Watson would need to navigate layers of gendered restrictions, requiring the narrative to either accommodate these limitations or radically revise them.

A female Watson does more than reshape plot mechanics; she invites the narrative to engage with contemporary gender issues. In modern reimaginings, she reflects the challenges faced by women in traditionally male-dominated fields such as medicine, law enforcement, or private investigation. Her presence brings into focus questions of credibility, authority, emotional labor, and partnership.

Joan Watson’s journey in Elementary explores professional identity, mentorship, and personal growth in ways not available to her male counterparts. She must not only prove herself to Holmes, but also to institutions that may doubt her competence. And while the relationship remains strictly platonic, its emotional richness defies simplistic archetypes. It is a partnership of equals, where gender informs character but does not define it.

This level of nuance would be difficult to sustain in a Victorian setting without veering into overt social critique. A female Watson of that era would likely face condescension, exclusion, or worse. Her very presence would shift the genre from detective fiction into a kind of proto-feminist social drama—an interesting transformation, but one that diverges sharply from the source material’s tone and structure.

Does a female Watson help or hinder Sherlock Holmes? The answer lies in how one defines the Holmes-Watson relationship. If the partnership is about intellectual admiration and emotional grounding, a female Watson enhances both. She challenges Holmes where he is weakest—not in deduction, but in human connection. She offers new perspectives, greater empathy, and a different way of interpreting the world.

Importantly, she is not a lesser version of Watson but a lateral transformation. The strength of the dynamic lies not in preserving the original formula, but in adapting it to new social and narrative contexts. A female Watson may provoke new tensions or emotional vulnerabilities in Holmes, but these do not weaken him—they humanize him. The essence of their partnership remains intact: different, yes, but equal.

Gender-swapping Watson is not simply a casting choice or a novelty twist—it is a narrative recalibration that brings fresh depth to the Sherlock Holmes mythos. While difficult to reconcile within the rigid gender norms of Victorian England, the female Watson thrives in modern settings where equality, complexity, and emotional nuance are not only accepted but expected.

In reimagining Watson as a woman, writers do not betray Conan Doyle’s legacy—they extend it. By adapting the character to reflect contemporary values and storytelling possibilities, they ensure the Holmes-Watson partnership remains relevant, resonant, and rich with new meaning. Like any great mystery, the thrill lies not in the expected answer, but in the unexpected path to its discovery.

Paul Bishop is the author of fifteen novels, including the award winning Lie Catchers. He is also the editor of 52 Weeks 52 Sherlock Holmes Novels—a multi-author compendium of essays regarding fifty-two of the best Sherlockian pastiches plus much more—Available on Amazon or from Genius Books...