Sherlock Holmes has left a curious and enduring imprint on Brazilian culture. From the early decades of the twentieth century to contemporary pastiches, the great detective has been reimagined, parodied, and transplanted into Brazilian settings in ways that reveal much about the nation’s literary imagination and cultural self-reflection.

In the years of Brazil’s First Republic, Holmes’ influence was already evident. Newspapers and crime writers eagerly adopted his methods of deduction, and the very idea of playing Sherlock became part of popular culture. The fascination with his reasoning created a phenomenon Brazilian critics and scholars later described as sherlockismo. The term captured not just the reading of Doyle’s detective stories, but also the way journalists, police commentators, and even ordinary readers tried to imitate Holmes’ methods in real life. Newspapers of the 1910s and 1920s often presented reports of crimes with a pseudo-deductive flair, inviting readers to follow along as though they too were solving the mystery. Holmes, then, was not confined to literature—he shaped how Brazilians thought about crime and criminality itself.

Academic studies of sherlockismo emphasize how this cultural borrowing was not neutral. On one hand, it demonstrated Brazil’s eagerness to adopt European models of rationality and modernity. On the other, it exposed tensions—Holmes’ cool logic and scientific detachment often clashed with local realities of crime reporting, where rumor, sensationalism, and improvisation carried as much weight as evidence. This mismatch created both comedy and critique. Holmes became a figure both admired and mocked, a symbol of Brazil’s attempt to modernize while wrestling with its own traditions of storytelling and justice.

A striking example of this interplay can be found in the collaborative novel O Mistério published in 1920 and written by Afrânio Peixoto, Viriato Correia, Medeiros e Albuquerque, and Coelho Netto. Its Sherlock of the city character is portrayed as incompetent, more clown than genius, and serves to lampoon Brazilian institutions that claimed rational authority but often fell short in practice. The novel exemplifies how Holmes’ figure could be harnessed to comment on the Brazilian judiciary and police, echoing the journalistic parodies of deduction that were widespread at the time. Scholars note that O Mistério was not an isolated case but part of a broader pattern in which Holmes’ shadow haunted Brazil’s developing genre of crime fiction.

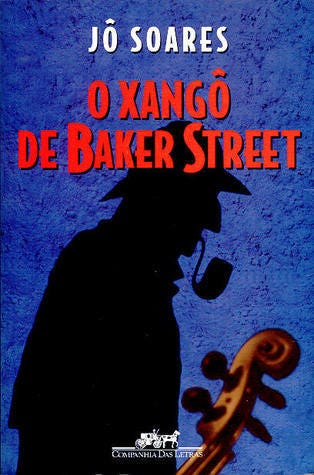

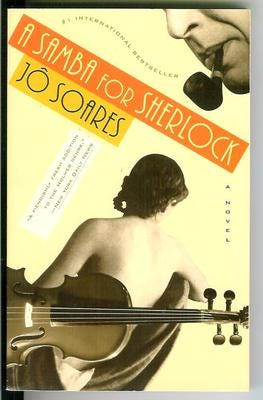

The most famous Brazilian reinvention of Sherlock Holmes came much later, in Jô Soares’s celebrated novel O Xangô de Baker Street. Published in 1995, the book transported Holmes and Watson to Rio de Janeiro in 1886, at the request of Emperor Dom Pedro II. Ostensibly summoned to recover a stolen violin, the pair soon found themselves entangled in a string of gruesome murders. Yet the novel’s true charm lies in its humor. Holmes fumbles under the tropical heat, tastes exotic foods, experiments with local drinks, and collides with Brazilian culture in ways both absurd and affectionate. The novel is not simply parody but also affectionate homage. By embedding Holmes within Brazil’s imperial history, Soares creates a playful dialogue between Victorian England and fin-de-siècle Rio de Janeiro, with all its contradictions—luxury alongside poverty, cosmopolitanism alongside provincialism.

The success of O Xangô de Baker Street confirmed Holmes could be both familiar and strange, an outsider whose foreignness illuminates national quirks. Its film adaptation in 2001 expanded this cultural presence, visually staging Holmes’ encounter with Rio’s vibrant landscapes and historical figures. To Brazilian audiences, the sight of the world’s most famous detective wandering through their own past carried a mixture of pride and satire—a reminder local culture was rich enough to host even the great Holmes, while also poking fun at his legendary self-confidence when placed in an alien context.

Beyond Soares’s work, Brazilian writers and comic artists have continued to engage with Holmes in inventive ways. Some place him within speculative settings, such as alternate histories or steampunk-inspired adventures—most notably the stories of Octavio Aragão, who included Holmes in the anthology Sherlock Holmes–Aventuras Secretas, reimagining the detective in fantastical scenarios. Others employ him as a figure of parody or political commentary.

The earlier novel O Mistério already revealed how Holmes could be used to lampoon Brazilian policing, while later works such as Noturno have used him to explore the anxieties of republican identity and national inferiority complexes in the aftermath of the Empire. In these reimaginings, Holmes ceases to be merely the British consulting detective, he becomes a cultural mirror, reflecting Brazil’s struggles with modernity, its playful spirit of parody, and its ongoing dialogue with global literary traditions.

This ongoing reworking of Holmes reflects a larger cultural phenomenon: Brazil’s openness to reinterpreting international icons within its own frameworks. Just as Brazilian musicians have absorbed and transformed jazz or rock into bossa nova and tropicalia, so too have Brazilian writers taken Sherlock Holmes and reshaped him to comment on their society. The detective’s deductive logic becomes a metaphor for foreign rationalism, his Victorian gentlemanliness a contrast with Brazilian improvisation, and his status as a global icon an invitation for playful cultural appropriation.

Taken together, these varied appearances of Sherlock Holmes in Brazilian culture show how a foreign character can be absorbed and transformed in unexpected ways. Holmes has been a satirical figure, a humorous tourist in nineteenth-century Rio, and a vehicle for speculative reimaginings. He has inspired journalistic practices, provoked academic reflection, and lent his shadow to Brazil’s own crime fiction traditions under the banner of sherlockismo. His deductive brilliance may belong to Baker Street, but his adaptability has allowed him to wander far beyond London—even to the streets of Brazil, where he continues to serve both as entertainment and as a spark for cultural reflection. In doing so, Holmes becomes not just a British detective but a transnational figure, capable of illuminating the peculiarities of any society he enters.

Through successive stages—journalistic inspiration, satirical pastiche, and creative homage—Sherlock Holmes moved from the printed page of British detective stories to a uniquely Brazilian literary and cultural phenomenon. He demonstrates not only the flexibility of Doyle’s creation but also Brazil’s capacity to adopt, transform, and ultimately claim a global icon as part of its own cultural imagination. In Brazil, Holmes has become more than a detective. He is a mirror, a provocateur, and a bridge, linking local history, humor, and literary creativity with the enduring appeal of one of literature’s most famous figures.

Paul Bishop is the author of fifteen novels, including the award winning Lie Catchers. He is also the editor of 52 Weeks 52 Sherlock Holmes Novels—a multi-author compendium of essays regarding fifty-two of the best Sherlockian pastiches plus much more—Available on Amazon or from Genius Books...